Cemetery

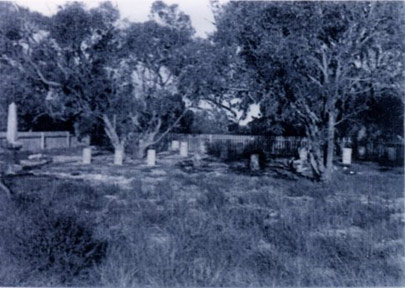

The first person to be buried in this cemetery was 25-year-old Harry Phillips in December 1918. He was one of 31 post-World War I Spanish influenza pandemic victims, the first 11 of whom were buried at East Rockingham cemetery, who died at Woodman Point Quarantine Station after becoming infected on the troopship ‘HMAT Boonah’.

Three female Army staff nurses (Rosa O’Kane, Doris Ridgway and Ada Thompson), and one civilian nurse (Hilda Williams), succumbed to the disease while caring for those troops. They were also buried at Woodman Point. Thompson was exhumed in 1920 and re-interred at Fremantle Cemetery. Most other service personnel were exhumed from this cemetery in 1958, and re-interred at Perth War Cemetery. The bodies of Rosa O’Kane and Hilda Williams remain at Woodman Point, the former marked by an impressive granite obelisk, and the latter by a simple wooden cross.

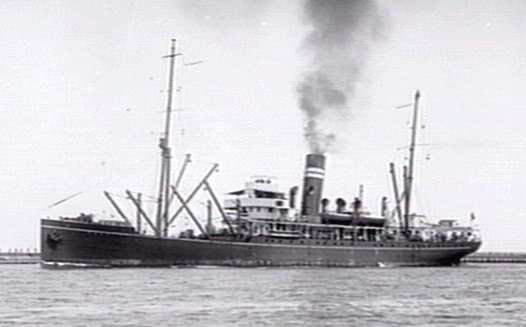

In 1943 four Fijian crewmen from the SS Suva, and their Chief Officer, died at Woodman Point from smallpox. They were the station’s last cremations. The crewmen’s ashes remain at Woodman Point in a single grave marked by a wooden plinth. The ashes of the Chief Officer were re-interred into a niche wall at Perth War Cemetery.

Extract from “Western Sentinel”

Source: Darroch, Ian. 2018. “Western Sentinel: A history of Woodman Point Quarantine Station”.

Faced with the prospect of even more deaths in the immediate future due to the unfurling Spanish Influenza crisis facing the former passengers of ‘HMAT Boonah’, it was becoming increasingly evident to military authorities a more convenient burial ground than the small East Rockingham cemetery was required.

Accordingly, a new cemetery was quickly consecrated in bushland within the quarantine station grounds and in less than twenty-four hours it was called into service. Private H.H. Phillips of South Australia had become the fourteenth victim to die at Woodman Point since the arrival of the Boonah, the toll now being heaviest among soldiers from that State. Much later and in another place, his headstone would bear the touching inscription:

"Loved in Life, Honoured in Death, Cherished in Memory.”

The onslaught of death showed no signs of lessening when on Thursday, 17 December 1918 Private Phillips was joined in his current resting place by four more of his former shipmates, including the second New Zealander, Trooper G. Blair. Also interred at the same time were Western Australian Private T.H. Hempsell and two Victorians, Private T. Corcoran and Corporal C.W. Lancaster. Within hours two more freshly dug graves enclosing the remains of A.F.C. Sergeant G.D. Moss of Healesville Victoria and young Railway Unit Private A.G. Wilson, would be added to the burgeoning row of Boonah victims laid to rest in this bushland setting. The very next day two more were added, with the passing of another Western Australian Private J. Clatworthy and Private Arthur Vernon from New South Wales.

After a brief respite of just three days, the citizens of Perth were again saddened by news the lives of two more young soldiers, Victorian Private C. Torney and Western Australian C.G.T. Nilsson, had been taken at Woodman Point. But apart from this latest tragedy, the general public was shocked to learn the first member of the quarantine medical staff, Sister Rosa O’Kane from Queensland, had also passed away. As one of the Wyreema volunteers, her death was deeply felt and served as a tragic omen to her hard-pressed and courageous colleagues. Too late, doctors and nurses on duty at the isolation hospital found the course of inoculations they had undertaken prior to taking up their duties did not provide them with full immunity. During the course of the outbreak twenty-nine members of the medical staff fell ill including another two military nurses Staff Sisters Ada Thompson and Doris Ridgeway and civilian nurse Hilda Williams; all three of whom would make the supreme sacrifice.

Details of the military funeral of Sister Rosa O’Kane appeared in the local press shortly after the service had been conducted alongside the graves of some of her former patients. (14) The daughter of a well-known editor and newspaper proprietor in her home town of Charters Towers, a special head stone was funded by public subscription organised by the town’s Patriotic Committee and supported by her fellow nurses and family friends in Queensland. Unwittingly, this non-military head stone disqualified her inclusion in the Perth War Cemetery many years later when the remains of fellow victims were reinterred there as representatives of the nation’s war-dead from the Great War. To this day, her tombstone stands in splendid isolation in the bushland setting of the old Woodman Point cemetery; still mute testimony to the sacrifice which took place there just weeks after the conflict of the First World War had ended.

An extract taken from a newspaper article marking the death of Staff Sister Doris Ridgeway, reported her burial in the following manner:

They lifted the little pitch-pine coffin covered with the Union Jack out of the wagon reverently and carried it through the white sand to its last resting place. The sun shone very sweetly on the blossoming bush and a bird pausing on its way to the sea beyond, stayed and mourned softly. Somehow, though the nursing sister friends were weeping, that was the only hopeless note that sounded at the burial of the little sister who had died while doing her simple duty...

The firing party who had led the way with reversed bayonets from the old quarantine hospital along the winding stone-flagged way to the little God’s acre of happy souls, looked down, and, as at a queen’s requiem, turned down also their guns, and, resting their hands quietly on them, stood so while the exquisite words of the service rang out...

The nursing sisters in grey dresses, white capped and red caped, wept but there was no hopeless sadness at the funeral of the little sister who had died doing her duty, rather would one wish that might be one’s own fate – to die nobly, peacefully, gloriously, and be buried in the sunshine by the sea...

The four stalwart lads who have lifted and lowered the beloved sister’s body in its shell, on which the white cap and scarlet cape now rested, to its last home, stood humbly by, their hands folded, their young faces stern with regret, and the sister friends bowed their heads sorrowfully weeping...

Then one by one the three volleys rent the air, the three volleys which tell a soldier that one of his comrades has been laid to rest and then like a sharp shower on an arid electric day, the rifles clattered to the salute, and the men in khaki presented arms to the still body which lay unheeding with feet set towards the dawn while the bugle rang out with its triumphant note, slowly sounding the Last post.

So do the bodies of some thirty valiant men and maids lie there at peace Men and maids who have done what they could...

...the little white sand mounds surrounded by blossoming shrubs, canopied by the blue sky of heaven, in the tiny square along the coast where the birds pause on their way to the sea beyond, give testimony that our land is ready to do or die, ready to fight and die if necessary, for the good of the common cause...

And all this because one little nurse was buried today beside the still forms of three other sisters who died while nursing Spanish influenza in Western Australia...

The Rev. J.A. Ford who was called upon to conduct their burial services of the army nurses, would later reflect:

“To me this striking case of courage and devotion to duty equals the action of a body of soldiers going over the top in trench warfare, the casualties being equivalent to those sustained in such an action – 3 killed and 12 wounded out of a detachment of 20. I count it an exceptional honour to have been associated with such a gallant band of sisters...”

More information

- Follow and interact with the Heritage Trail on the NaturePlayWA App.

- Heritage content compiled by Woodman Point Recreation Camp, in collaboration with the Friends of Woodman Point Recreation Camp Inc.

- Images sourced from archival and personal collections held by the Friends of Woodman Point Recreation Camp.

- ‘Western Sentinel: A history of the Woodman Point Quarantine Station, Western Australia 1852-1979’ by Ian Darroch, is available for purchase from Woodman Point Recreation Camp. Proceeds to the Friends of Woodman Point Recreation Camp to conserve and promote the heritage of the Quarantine Station.